But you need to keep reading to find out how we're giving you more candy, not coal this month.

Besides the lead article featured on this post, Mr. Pratt reviews more than three dozen movies/TV/media releases in his newsletter including Furious 7, the latest release in The Fast and Furious Franchise that long ago retired the theory that sequels can't race past the original model. Mr. Pratt even likes this latest release better than Mad Max: Fury Road. “As thrilling and inventive as a James Bond movie, but with heart.” His review also covers the impact the tragic death of Paul Walker had on the production.

John Sturges is a filmmaker rarely considered a true film auteur. He directed two of my favorite films of all time -- THE GREAT ESCAPE and The Magnificent Seven. There’s no doubt that his work as a director influenced many successful filmmakers who followed including Steven Spielberg and Clint Eastwood. However, John Sturges was a filmmaker who specialized in producing and directing action movies, which Hollywood has kept getting better and better at making over the years. I believe this has led to many films directed (and produced) by Sturges that now come off as dated when viewed by modern audiences.

John Sturges is a filmmaker rarely considered a true film auteur. He directed two of my favorite films of all time -- THE GREAT ESCAPE and The Magnificent Seven. There’s no doubt that his work as a director influenced many successful filmmakers who followed including Steven Spielberg and Clint Eastwood. However, John Sturges was a filmmaker who specialized in producing and directing action movies, which Hollywood has kept getting better and better at making over the years. I believe this has led to many films directed (and produced) by Sturges that now come off as dated when viewed by modern audiences. Mr. Pratt reviews The Satan Bug, praising the undeniable strength of the movie -- “the story advances steadily under Sturges’ confident staging, and the film even has something of a cult following because of the way in which its narrative sustains its compelling momentum." Sturges directed The Satan Bug after TGE and TM7 and is the type of film that I believe has hurt the chances of Sturges ever being considered a "great filmmaker."

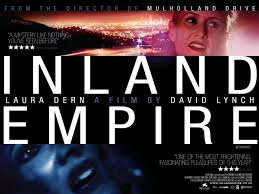

Speaking of artistic auteurs, David Lynch, long ago became a member of that club. I’m such a huge fan of his accomplishments as a filmmaker that I will confess to loving a movie even many of his fans hate -- Dune. Regardless of how much we probably disagree on that film, I bring the movie up for another reason – Dune was considered a creative disaster when it was first released and was a major disappointment at the box office. What Lynch did in the wake of that disaster is what many successful artists do – they learn from their ambitious ventures (especially when they turn out to be a failure) using the past to inform their future work. After the movie was released, Lynch rededicated his career to focusing on making movies that would draw on his unique talents as a filmmaker, never again attempting to direct a huge, big budgeted production.

Speaking of artistic auteurs, David Lynch, long ago became a member of that club. I’m such a huge fan of his accomplishments as a filmmaker that I will confess to loving a movie even many of his fans hate -- Dune. Regardless of how much we probably disagree on that film, I bring the movie up for another reason – Dune was considered a creative disaster when it was first released and was a major disappointment at the box office. What Lynch did in the wake of that disaster is what many successful artists do – they learn from their ambitious ventures (especially when they turn out to be a failure) using the past to inform their future work. After the movie was released, Lynch rededicated his career to focusing on making movies that would draw on his unique talents as a filmmaker, never again attempting to direct a huge, big budgeted production. Years later, Lynch agreed to shepherd a TV series, and shot a pilot. When the Network did not pick up the project for a TV series, Lynch was once more faced with “failure.”

And once again, he turned failure… into success.

I’ll let Doug Pratt take the story from there with his review of MULHOLLAND DR.. But be sure to keep reading beyond the review to find a special treat this month –

CAPSULE EXCERPTS from Doug Pratt's past reviews of key projects in the strange and influential career of filmmaker/icon, David Lynch.

Never saw a woman so alone

Every movie is observed with emotional responses from a viewer. All forms of art elicit an emotional response, but because film is a combination of so many different art forms, the intensity of the emotional response is raised exponentially. Hence, every time you see the same film, you see it and feel it differently. The subsequent times you see the same movie, those emotions are altered by your memories and feelings toward the previous viewings. For most movies, those feelings don’t change all that much. Heck, it may be that the film’s trailer has already taught you what to think or feel about the film, and the first time through or the seventh time through, the expectations and reactions are unchanged. But then there are movies that change every time you watch them, because you are so overwhelmed with feelings about everything that is going on, you cannot process it all the first time through, especially when you have no idea, the first time through, where the movie is going to take you.

Even when you realize, in the last act, that most of David Lynch’s 2001 masterpiece—one of several masterpieces he has created over the years—MULHOLLAND DR., is a dream, you do not know it before then (sure, a couple of characters say they are in a dream at a couple of different points, but how can you know those are the statements you are supposed to pay attention to?), and so the first time you experience the movie is very different from the next time you experience it. And after that, the depth of detail is nearly impossible to absorb in its entirety for the full 146 minutes, and so you watch the movie again and again, seeing and feeling new things about it each time.

A literal description of the film’s narrative would be that Naomi Watts portrays an aspiring actress who arrives at Los Angeles to stay in her aunt’s vacated apartment while she tries to get her career started. She discovers another woman staying there, who was involved in an accident on Mulholland just as, apparently, some men were about to kill her. The woman has amnesia, and the two become sleuths, trying to determine who the woman is and why she has an enormous amount of money in her purse. Laura Harring co-stars. There are a few digressions—the background experiences of other characters who then interact with the two heroines; there is also, at about the 12-minute mark, one of the most frightening moments ever created on film, if you want to give your friends a good scare—but the story proceeds delightfully. Watts’ character nails an audition, and she and Harring have a very steamy interlude while they come closer and closer to solving the mystery. And then,

poof! Watts’ character is suddenly not living in such a nice apartment, and Harring’s character, although she is still having sex with her, is more dismissive and controlling. The other peripheral characters are the same but different, and there was no accident on Mulholland Drive.

It was Ann Miller’s last film, and she has a wonderful supporting part, as do Chad Everett and Lee Grant. Justin Theroux is featured as a movie director with a host of problems of his own, along with Dan Hedaya, Mark Pellegrine, and Brent Briscoe. Robert Forster and Billy Ray Cyrus are seen briefly, and Angelo Badalamenti, who wrote the film’s succulent musical score, gets to play a gangster, too.

Universal released a fine DVD version in 2002. It had a gorgeous picture and even DTS sound. The Criterion Collection has nevertheless released a long awaited Blu-ray (UPC#715515159319, $30), and both the picture and the sound are even better. The image is sharper, with better defined hues and more detail. The DTS sound is crisper, denser, and also seems to have more going on. Like the DVD, and undoubtedly at Lynch’s request, there is no chapter encoding. There are optional English subtitles, a bewitching trailer, a 2-minute deleted scene with Forster that was irrelevant to the film, and a terrific 25-minute collection of behind-the-scenes footage that specifically shows Lynch setting up shots and working with the actors. Lynch even gets annoyed at the video guy for eavesdropping a couple of times as he powwows with Watts and others.

As entertaining and even riveting as anything you can watch on TV, Lynch and Watts sit for a 27-minute interview and conversation about the film, Watts’ career (this was the movie that made her a star, just like the fantasy version of her character), and moviemaking. What they have to say is always stimulating and informative, but more importantly, the piece captures either their real relationship or two exquisite performances of a real relationship. Either way, it is a delightful and even thrilling portrait of a genuine friendship that contradicts the notorious, yet functionally necessary, superficiality of Hollywood.

A 36-minute piece begins as a profile of casting director Johanna Ray and then shifts into interviews with various cast members, talking about their experiences landing their roles and working with Lynch. Badalamenti speaks for 19 minutes, and also plays passages from the score, as he goes over the beginning of his career, how he started working with Lynch, how he approached the music in MULHOLLAND DR., and he also shares a marvelous anecdote about why Lynch cast him as the gangster. Cinematographer Peter Deming is intercut with production designer Jack Fisk for a 22-minute interview piece, in which both talk about Lynch’s design strategies and the work they had to do to accommodate him on the film, as well as how they started working with him and specific anecdotes about the shoot. Fisk actually went to junior high school with Lynch and hung out with him then. Deming is about the only person in any of the pieces to really talk about the differences between the film and the TV pilot (there is more detail about it in a jacket insert, however), speculating about what the series might have been like (stars like Forster and Cyrus would have had a lot more to do), and if the BD has any shortcoming, it is that the pilot itself wasn’t also included as a special feature. After all, this is a movie that was begun by dreaming it was a TV series.

What a Strange and Weird Trip it's been Following the Filmmaking Career of David Lynch.

The 1977 film began its theatrical life in midnight screenings and was therefore known only to a certain breed of moviegoer willing to expend an uncommon level of personal commitment to view it. Hence, when Eraserhead appeared on home video a few years later and became the subject of conversation with movie fans who would never think of leaving their homes after 11:00 at night, it represented a monumental shift in how movies are seen and digested, one that raised the level of aptitude and film literacy throughout the world.

If you are a true fan of Dune, you owe it to yourself to watch the film some day entirely in black and white. Not only are some of the special effects a great deal more impressive, but the dream sequences are much stronger, the focal point of a scene or a shot is made more clear (although the sets are elaborately colored, you suddenly realize that the central characters are strikingly illuminated in contrast to the backgrounds), and the entire atmosphere of the film becomes even more exotic than it already is.

David Lynch’s magnificently textured mystery is a brilliant send off on juvenile crime stories such as The Hardy Boys, taking the innocence of that peculiar form of Americana and turning it on its head. Some reserved observers may question the need for experiencing the emotions the film kindles. The point is that the emotions are there anyway, hidden or in the open. BLUE VELVET has got to be one of the best movies about the final stages of growing up.

David Lynch's worst movie has a flat out, gorgeous picture transfer. All the grain, all the fuzz and all the bad looking fleshtones of the movie’s previous home video iterations (and even its theatrical presentations) are gone and forgotten, blown away like Willem Defoe’s head by the vivid, luxuriant and meticulous image transfer.

Created by Lynch and Mark Frost, the program has a poetic strength that carries

it beyond a simple familiarity with its narrative and characters. It is a

running parody of the soap opera form, but it is rendered with an eerie,

abstract attention to detail and atmosphere. There seems to be some resentment and anger in Lynch over the series having to

end, which adds greatly to the

Created by Lynch and Mark Frost, the program has a poetic strength that carries

it beyond a simple familiarity with its narrative and characters. It is a

running parody of the soap opera form, but it is rendered with an eerie,

abstract attention to detail and atmosphere. There seems to be some resentment and anger in Lynch over the series having to

end, which adds greatly to the(final) episode’s grandly satirical spirit. Almost all of the characters have terrible things happen to them, and McLaughlin’s character—well, there’s never really been anything else like that on television, to say the least.

Every morning we wake up and say a blessing because we live in

a country and an economic system where a movie such as TWIN PEAKS FIRE WALK WITH ME can be produced. Appealing only to a subset of a subset of Twin Peaks and David Lynch fans, the film is a narrative disaster, Artistically, the film is a coherent blend of emotions and images, evoking the dead ends in dreams and the terrors of nightmares. It is Lynch’s masterpiece.

This is the way movie history works. Every once in a while, a film will be made by an exceptionally talented director that is so eccentric, even for the director’s own work, it will be met with widespread critical derision or indifference, and will fail so completely at the boxoffice that it does not play at all in several major American cities. It will be in release on DVD for two weeks and yet the clerks at the local Blockbuster will have never heard of it, and certainly will not have it in stock. But four or five decades down the road, it will be one of only a half-dozen films from that year that people still watch on a regular basis and share with their friends, and it will, perhaps, be the only title from that year that will be studied and analyzed in academia. Such is to be the fate, guaranteed, of David Lynch’s 2006 feature

No comments:

Post a Comment